|

Page

23

Secrets

of the 'other you'

Tom

lethbridge's own explanation of this strange 'power of the

pendulum' Is that there is a part of the human mind - the

uncons-cious, perhaps - that knows the answers to all

questions. Unfortunately it cannot convey these answers to

the 'everyday you', the busy, conscious self that spends its

time coping with practical problems. But this 'other you'

can convey its message via the dowsing rod or

pendulum by the simple expedient of controlling the

muscles.

Lethbridge

had started as a cheerfully sceptical investigator trying to

understand nature's hidden codes for conveying information .

His researches led him into strange, bewildering realms

where all his normal ideas seemed to be turned upside down.

He compared himself to a man walking on ice, when it

suddenly collapses and he finds himself floundering in

freezing water. Of this sudden immersion in new ideas he

said: 'From living a normal in a three- dimensional world, I

seem to have suddenly fallen through into one where there

are more dimensions. The three dimensional life goes on as

usual; but one has to adjust one's thinking to the other.'

"

Page

25

"...Lethbridge

had always been interested in dreams, ever since he read J.

W. Dunne's An experiment with time in the 1930's"

"...Lethbridge speculated that during sleep, a part of us

passes through this world to a still higher world still.

Coming back from sleep we pass through it once again to

enter our own much slower world of

vibrations."

Page

27

"...The

more he studied these puzzles, the more convinced Lethbridge

became that the key to all of them is the concept of

vibrations. Our bodies seem to be machines tuned to

pick up certain vibrations. Our eyes will only register

energy whose wavelength is between that of red and violet

light. Shorter or longer wavelengths are invisible to us.

Modern Physics tells us that at the sub- atomic level matter

is in a state of constant

vibration.

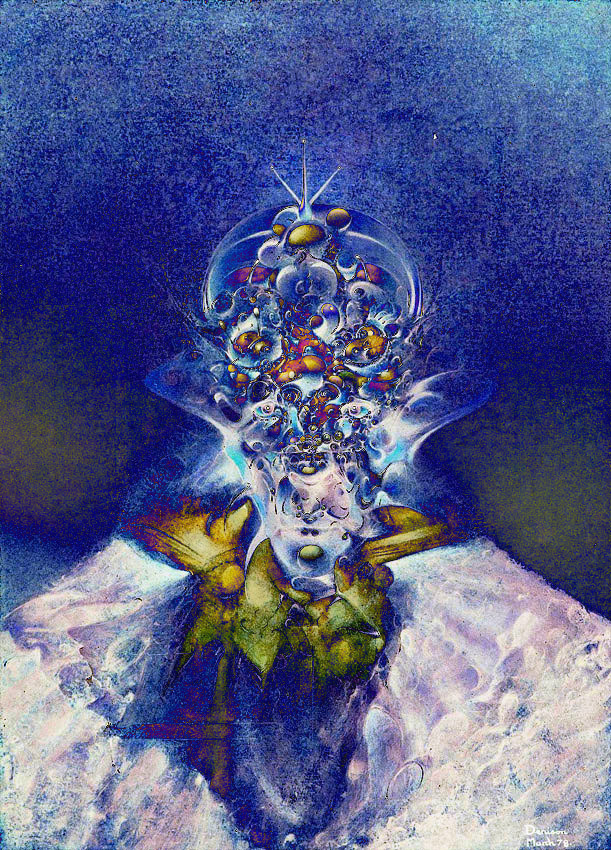

Diagram

and photographs omitted

"...the

spectrum of electromagnetic (EM) vibrations. EM waves

consist of electric and magnetic fields vibrating with a

definite frequency, each corresponding to a particular

wavelength in order of increasing frequency and decreasing

wavelength, the EM spectrum consists of : very long wave

radio, used for communication with submarines; long, medium

and short wave radio (used for AM broadcasting); FMradio,

television and radar; infra-red (heat) radiation, which is

recorded in the Earth photographs taken by survey

satellites; visible light; ultraviolet light, which, while

invisible, stimulates fluorescence in some materials; X-

rays; and high energy gamma rays, which occur in fall out

and in cosmic rays. The progressive discovery of these waves

has inspired speculations concerning unknown 'vibrations'

making up our own and higher worlds"

Worlds

beyond worlds

According

to Lethbridge's pendulum, the 'world' beyond our world - the

world that can be detected by a pendulum of more than 40

inches - consists of vibrations that are four times as fast

as ours. It is all around us yet we are able to see it,

because it is beyond the range of our senses. All the

objects in our world extend into this other world. Our

personalities also extend into it, but we are not aware of

this, because our 'everyday self' has no communication with

that 'other self'. But the other self can answer questions

by means of the pendulum."

"...Lethbridge's

insistence on rediscovering the ancient art of dowsing also

underlined his emphasis on understanding the differences

between primitive and modern Man. The ancient peoples- going

back to our caveman ancestors - believed that the Universe

is magical and that Earth is a living creature. They were

probably natural dowsers - as the aborigines of australia

still are - and res-ponded naturally to the forces of the

earth. Their standing stones were, according to Lethbridge,

intended to mark places where the earth force was most

powerful and perhaps to harness it in some way now

forgotten.

Modern Man has suppressed - or lost that instinctive,

intuitive contact with the forces of the Universe. He is two

busy keeping together his precious civilisation Yet he still

potentially possesses that ancient power of dowsing, and

could really develop it if he really wanted to. Lethbridge

set out to develop his own powers, and to explore them

scientifically, and soon came to the conclu-sion that the

dowsing rod and the pendulum are incredibly accurate. By

making use of some unknown part of the mind - the

un-conscious or 'superconscious' - they can provide

information that is inaccessible to our ordinary senses, and

can tell us about realms of reality beyond the 'everyday'

world of physical matter.

Lethbridge

was not a spiritualist. He never paid much attention to the

question of life after death or the existence of a 'spirit

world'. But by pursuing his researches into these subjects

with a tough - minded logic, he concluded that there are

other realms of reality beyond our world, and that there are

forms of energy we do not even begin to understand. Magic,

spiritualism and occult-ism are merely our crude attempts to

under-stand this vast realm of hidden energies, just as

alchemy was Man's earliest attempt to understand the

mysteries of atomic physics.

As

to the meaning of all this, Lethbridge preserves the caution

of an academic. Yet in his last years he became increasingly

con-vinced that there is a meaning in human existence. and

that it is tied up with the concept of our personal

evolution. For some reason we are being driven to

evolve.

With

a bow, instead of a wob those twa brothers, and one sister

being caught fast, rainbowed out and in order not to

lose that golden thread of threads. Alizzed here

re-introduced that beloved Mann, Castorp.

THE MAGIC MOUNTAIN

Thomas Mann 1924

Humaniora

THE MAGIC MOUNTAIN

Thomas Mann 1924

Humaniora

Page 251 /

" HANS CASTORP and Joachim Ziernssen, arrayed in white trouse and blue blazers, were sitting in the garden after

dinner. It was another of those much-lauded October days: bright without be-ing heavy, hot and yet with a tang in the air. The sky

above the vally was a deep southern blue and the pastures beneath, widt the cattle tracks running across and across them, still a

lively green. From the rugged slopes came the sound of cowbells; the peacefu, simple, melodious tintinnabulation came floating

unbroken through the quiet, thin, empty air, enhancing the mood of solemnity that broods over the valley heights.

The

cousins were sitting on a bench at the end of the garden, in

front of a semi-circle of young firs. The small open space

lay at the north-west of the hedged-in platform, which rose

some fifty yards above the valley, and formed the

foundations of the Berghof building. They were silent. Hans

Castorp was smoking. He was also wrangling inwardly with

Joachim, \\lho had not wanted to join the society on the

verandah after luncheon, and had drawn his cousin against

his will into the stillness and seclusion of the garden,

until such time as they should go up to their balconies.

That was behaving like a tyrant - when it came to that, they

were not Siamese twins, it was possible for them to

separate, if their inclinations took them in opposite

directions. Hans Castorp was not up here to be company for

Joachim, he was a patient hiinself.

/

Page 252 /

Thus

he grumbled on, and could endure to grumble, for had he not

Maria? He sat, his hands in his blazer pockets, his feet in

brown shoes stretched out before him, and held the long,

greyish cigar between his lips, precisely in the centre of

his mouth, and droop- ing a little. It was in the first

stages of consumption, he had not yet knocked off the ash

from its blunt tip; its aroma was pec-uliarly grateful after

the heavy meal just enjoyed. It might be true that in other

respects getting used to life up here had mainly consisted

in getting used to not getting used to it. But for the

chemistry of his digestion, the nerves of his mucous

membrane, which had been parched and tender, inclined to

bleeding, it seemed that the process of adjustment had

completed itself. For imperceptibly, in the course of these

nine or ten weeks, his organic satisfaction in that

excellent brand of vegetable stimulant or narcotic had been

entirely restored. He rejoIced in a faculty regained, his

mental satisfaction heightened the physical. During his time

in bed he had saved on the supply of two hundred cigars

which he had brought with him, and some of these were still

left; but at the same time with his winter clothing from

below, there had arrived another five hundred of the Bremen

make, which he had ordered through Schalleen to make quite

sure of not running out. They came in beautiful little

varnished boxes, ornamented in gilt with a globe, several

medals, and an exhibition building with a flag floating

above it.

As

they sat, behold, there came Hofrat Behrens through the

garden. He had taken his midday meal in the dining-hall

to-day, folding his gigantic hands before his place at Frau

Salomon's table. After that he had probably been on the

terrace, making the suitable personal remark to each and

everybody, very likely displaying his trick with the

bootlaces for such of the guests as had not seen it. Now he

came lounging through the garden, wear- ing a check

tail-coat, instead of his smock, and his stiff hat on the

back of his head. He too had a cigar in his mouth, a very

black one, from which he was puffing great white clouds of

smoke. His head and face, with the over-heated purple

cheeks, the snub nose, watery blue eyes, and little clipped

moustache, looked small in proportjon to the lank, rather

warped and stooping figure, and the enormous hands and feet.

He was nervous; visibly started when he saw the cousins, and

seemed embarrassd over the neces-sity of passing them. But

he greeted them in his usual picturesque and expansive

fashion, with "Behold, behold, Timotheus! " go- ing on to

invoke the usual blessings on their metabolisms,

while

/

Page 253 /

he

prevented their rising from their seats, as they would have

done in his honour.

"Sit

down, sit down. No formalities with a simple man like me.

Out of place too, you being my patients, both of you. Not

necessary. No objection to the status quo," and he remained

stand- ing before them, holding the cigar between the index

and middle fingers of his great right

hand.

"

How's your cabbage-leaf, Castorp? Let me see, I'm a

connois-seur. That's a good ash - what sort of brown beauty

have you there? "

"Maria

Mancini, Postre de Banquett, Bremen, Herr Hofrat.

Costs little or nothing, nineteen pfennigs in plain colours

- but a bouquet you don't often come across at the price.

Sumatra-Havana wrapper, as you see. I am very wedded to

them. It is a medium mixture, very fragrant, but cool on the

tongue. Suits it to leave the ash long, I don't knock it off

more than a couple of times. She has her whims, of course,

has Maria; but the inspection must be very thorough, for she

doesn't vary much, and draws perfectly even May I offer you

one? "

"

Thanks, we can exchange." And they drew out their

cases.

"There's

a thorough-bred for you," the Hofrat said, as he displayed

his brand. " Temperament, you know, juicy, got some guts to

it. St. Felix, Brazil- I've always stuck to this sort.

Regu-lar 'begone, dull care,' burns like brandy, has

something ful- minating toward the. end. But you need to

exercise a little cau- tion - can't light one from the

other, you know - more th:tn a fellow can stand. However,

better one good mouthful than any amount of

nibbles."

They

twirled their respective offerings between their fingers,

felt connoisseur-like thc slender shapes that possessed, or

so one might think, some organic quality of life, with their

ribs fonned by the diagonal parallel edges of the raised,

here and tbere porous wrapper, the exposed veins that seemed

to pulsate, the small in- equalities of the skin, the play

of light on planes and edges.

Hans

Castorp expressed it: "A cigar like that is alive- it

breathes. Fact. Once, at home, I had the idea of keeping

Maria in an air-tight tin box, to protect her from damp.

Would you believe it, she died! Inside of a week she

perished - nothing but leathery corpses

left."

They

exchangcd experiences upon the best way to keep cigars -

particularly imported ones. The Hofrat loved them,. he would

have smoked nothing but heavy Havanas, but they did not suit

/

Page 254 /

him.

He told Hans Castorp about two little Henry Clays he had

once taken to his heart, in an evening company, which had

come within an ace of putting him under the

sod.

..

I smoked them with my coffee, " he said, and thought no more

of it. But after a while it struck me to wonder how I felt -

and I discovered it was like nothing on earth. I don't know

how I got home - and once there, well, this time, my son, I

said to myself, you're a goner. Feet and legs like ice, you

know, reeking with cold sweat, white as a table-cloth, heart

going all ways for Sunday - sometimes just a thread of a

pulse, sometimes pounding like a trip- hammer. Cerebration

phenomenal. I made sure I was going to toddle off - that is

the very expression that occurred to me, be-cause at the

time I was feeling as jolly as a sand-boy. Not that I wasn't

in a funk as well, because I was - I was just one large blue

funk all over. Still, funk and felicity aren't mutually

exclusive, everybody knows that. Take a chap who's going to

have a girl for the first. time in his life; he is in a funk

too, and so is she, and yet both of them are simply

dissolving with felicity. I. was nearly dis-solving too - my

bosom swelled with pride, and there I was, on the point of

toddling off; but the Mylendonk got hold of me and - suaded

me it was a poor idea. She gave me a camphor injection,

applied ice-compresses and friction - and here I am, saved

for hu- manity ."

The Hofrat's large, goggling blue eyes watered as he told this story. Hans Castorp, seated in his capacity of patient, looked up at

him with an expression that betrayed mental activity.

" You paint sometimes, don't you, Herr Hofrat? " he asked suddenly.

The Hofrat pretended to stagger backwards " W hat the deuce! What do you take me for, youngster? "

" I beg your pardon. I happened to hear somebody say so, and it just crossed my mind."

"Well,

then, 1 won't trouble to lie about it. We're all poor crea-

tures. I admit such a thing has happened. Anch' io sono

pittore, as the Spaniard used to

say.'

"

Landscape? " Hans Castorp asked him succinctly, with the air

of a connoisseur, circumstances betraying him to this

tone.

" As much as you like," the Hofrat answered, swaggering out of sheer self-consciousness. " Landscape, still life, animals - chap

like me shrinks from nothing."

" No portraits? "

"I've

even thrown in a portrait or so. Want to give me an order?"

/

Page 255 /

Ha

ha! No, but it would be very kind of you to show us your

pictures some time - we should enjoy it." Joachim looked

blankly at his cousin, but then hastened to add his

assurances that it would be very kind indeed of the

Hofrat.

Behrens

was enchanted at the flattery. He grew red with pleas- ure,

his tears seemed this time actually on the point of

falling.

"With

the greatest pleasure," he cried. On the spot if you like.

Come on, come along with me, I'll brew us a Turkish coffee

in my den."

He

pulled both young men from the bench and walked be-tween

them arm in arm, down the gravel path which led, as they

knew, to his private quarters in the north-west wing of the

build- mg.

"

I've dabbled a little in that sort of thing myself," Hans

Castorp explained.

"You

don't say! Gone in for it properly - oils?

"

"

Oh, no, I never went further than a water-colour or so. A

ship, a sea-piece, childish efforts. But I'm fond of

painting, and so I took the liberty -

"

Joachim

in particular felt relieved and enlightened by this ex-

planation of his cousin's startling curiosity; it was in

fact more on his account than on the Hofrat's that Hans

Castorp had offered it. They reached the entrance, a much

simpler one than the impres-sive portal on the drive, with

its flanking lanterns. A pair of curv-ing steps led up to

the oaken house door, which the Hofrat opened with a

latch-key from his heavy bunch. His hand trembled, he was

plainly in a nervous state. They entered an antechamber with

clothes-racks, where Behrens hung his bowler on a hook, and

thence passed into a short corridor, which was separated by

a glass door from that of the main building. On both sides

of this corridor lay the rooms of the small private

dwelling. Behrens called a servant and gave an order; then

to a running accompaniment of whimsical remarks ushered them

through a door on the right.

They

saw a couple of rooms furnished in banal middle-class taste,

facing the valley and opening one into another through a

doorway hung with portieres. One was an "old-German"

din-ing-room, the other a living- and working-room, with

woollen carpets, bookshelves and sofa, and a writing-table

above which hung a pair of crossed swords and a student's

cap. Beyond was a Turkish smoking-cabinet. Everywhere were

paintings, the work of the Hofrat. The guests went up to

them at once on entering, courteously ready to praise. There

were several portraits of his de-parted wife, in oil; also,

standing on the writing-table, photo-

/

Page 256 /

graphs

of her. She was a thin, enigmatic blonde, portrayed in

flow-ing garments, with her hands, their finger-tips just

lightly enlaced, against her left shoulder, and her eyes

either directed toward heaven or else cast upon the ground,

shaded by long, thick, ob-liquely outstanding eyelashes.

Never once was the departed one shown looking directly ahead

of her toward the observer. The other pictures were chiefly

mountain landscapes, mountains in snow and mountains in

summer green, mist-wreathed mountains, mountains whose dry,

sharp outline was cut out against a deep-blue sky - these

apparently under the influence of Segantini. Then there were

cowherds' huts, and dewlapped cattle standing or lying in

sun-drenched high pastures. There was a plucked fowl, with

its long writhen neck hanging down from a table among a

setting of vegetables. There were flower-pieces, types of

mountain peasantry, and so on - all painted with a certain

brisk dilettantism, the colours boldly dashed on to the

canvas, and often looking as though they had been squeezed

on out of the tube. They must have taken a long time to dry

- but were sometimes effective by way of helping out the

other shortcomings.

They

passed as they would along the walls of an exhibition,

ac-companied by the master of the house, who now and then

gave a name to some subject or other, but was chiefly

silent, with the proud embarrassment of the artist, tasting

the enjoyment of look- ing on his own works with the eyes of

strangers. The portrait of Clavdia Chauchat hung on the

window wall of the living-room - Hans Castorp spied it out

with a quick glance as he entered, though the likeness was

but a distant one. Purposely he avoided the spot, detaining

his companions in the dining-room, where he affected to

admire a fresh green glimpse into the valley of the Serbi,

with ice- blue glaciers in the background. Next he passed of

his own accord into the Turkish cabinet, and looked at an it

had to show, with praises on his lips thence back to the

living-room, beginning with the entrance wall, and calling

upon Joachim to second his en- comiums. But at last he

turned, with a measured start, and said: "But surely that is

a familiar face? "

"You recognize her? "the Hofrat wanted to know.

" It is not possible I am mistaken. The lady at the' good' Rus-sian table, with the French name - "

Right! Chauchat. Glad you think it's like her."

Speaking,"

Hans Castorp lied. He did so less from insincerity than in

the consciousness that, on the face of things, he ought not

to have been able to recognize her. Joachim could never have

done so - good Joachim, who saw the whole affair now in its

true light,

/

Page 257 /

after

the false one Hans Castorp had first cast upon it; wool had

been pulled over his eyes; and with a murmured recog-nition

applied himself to help look at the painting. His cousin had

paid him out for not going into society after luncheon. It

was a bust-length, in half profile, rather under life size

in a wide, bevelled frame, black, with an inner beading of

guilt. Neck and bosom were bare or veiled with a soft

drapery laid about the shoulders. Frau Chauchat appeared ten

years older than her age, as often happens in amateur

portraiture where the artist is bent on making a character

study. There was too much red all over the face, the nose

was badly out of drawing, the colour of the hair badly hit

off, too straw-colour; the mouth was distorted, the

pecu-liar charm of the features ungrasped or at least not,

spoiled by the exaggeration of their single elements. The

whole was a rather botched performance, and only distantly

related to its original. But Hans Castorp was not particular

about the degree of like-ness, the relation of this canvas

to Frau Chauchat's person was close enough for him. It

purported to represent her, in these very rooms she had sat

for it, that was all he needed; much moved he

reiterated:

"

The very image of her! "

"Oh,

no," the Hofrat demurred. "It was a pretty clumsy piece of

work, I don't flatter myself I hit her off very well we had,

I suppose, twenty sittings. What can you do with a rum sort

of face like that? You might think she would be easy to

capture, with those hyperborean cheek-bones, and eyes like

cracks in a loaf of bread. Yes, there's something about her-

if you get the detail right, you botch the ensemble. Riddle

of the sphinx. Do you know her? It would probably be better

to paint her from memory instead of having her sit. Did you

say you knew her? "

"

No; that is, only superficially, the way one knows people up

here."

"Well,

I know her under her skin - subcutaneously, blood pressure,

tissue tension, lymphatic circulation, al that sort of

thing. I've good reason to. It's the superficies make the

difficulty. Have you ever noticed her walk? She slinks. It's

character - istic, show's in her face - take the eyes, for

example, not to mention the complexion, though that is

tricky too. I don't mean their colour, I am speaking of the

cut, and the way they s it in the faceYou'd say the eye slit

was cut obliquely, but it only looks so. What deceives you

is the epicanthus, a racial variation, consisting in a sort

of ridge of integument that runs from the bridge of the nose

to the eyelid, and comes down over the inside corner of the

eye. If you take your finger and stretch the skin at the

base of the nose, the

/

Page 258 /

eye

looks as straight as any of ours. Quite a taking little

dodge - but as a matter of fact, the epicanthus can be

traced back to an atavistic vestige - it's a. developmental

arrest."

"

So that's it. " Hans Castorp said. "I never knew that - but

I've wondered for a long time what it is about eyes like

that."

"

Vanity," said the Hofrat, and vexation of spirit. If you

simply draw them in slanting, you are lost. You must bring

about the obliquity the same way nature does, you must add

illusion to illusion - and for that you have to know about

the epicanthus. What a man knows always comes in handy. Now

look at the skin - the epidennis. Do you find I've managed

to make it lifelike, or not? "

"

Enormously," said Hans Castorp, "Simply enormously. I've

never seen skin painted anything like so well. You can

fairly see the pores..' And he ran the edge of his hand

lightlyy over the bare neck and shoulders, the skin of

which, especially by contrast with the exaggerated red of

the face, was very white, as though seldom exposed. Whether

this effect was premeditated or not, it was rather

suggestive.

And

still Hans Castorp's praise was deserved. The pale shim-mer

of this tender, though not emaciated, bosom, losing itself

in the bluish shadows of the drapery, was very like life. It

was obvi-ously painted with feeling; a sort of sweemess

emanated .from it, yet the artist had been successful in

giving it a scientific realism and precision as well. The

roughness of the canvas texture, show-ing through the paint,

had been dexterously employed to suggest the natural

unevennesses of the skin - this especially in the neigh-

bourhood of the delicate collar-bones. A tiny mole, at the

point where the breasts began to divide, had been done with

care, and on their rounding surfaces one thought to trace

the delicate blue veins. It was as though a scarcely

perceptible shiver of sensibility beneath the eye of the

beholder were passing over this nude flesh, as though one

might see the perspiration, the invisible vapour which the

life beneath threw off; as though, were one to press one's

lips upon this surface, one might perceive, not the smell of

paint and fixative, but the odour of the human body. Such,

at least, were Hans Castorp's impressions, which we here

reproduce - and he, of course, was in a peculiarly

susceptible state. But it is none the less true that Frau

Chauchat's portrait was by far the most telling piece of

painting in the room.

Hofrat

Behrens rocked back and forth on his heels and the balls of

his feet, his hands in this trouser pockets, as he gazed at

his work in company with the

cousins.

/

Page 259 /

"

Delighted," he said. "Delighted to find favour in the eyes

of a colleague. If a man knows a bit about what goes on

under the epidermis, that does no harm either. In other

words, if he can paint a little below the surface, and

stands in another relation to nature than just the lyrical,

so to say. An artist who is a doctor, physi-ologist, and

anatomist on the side. and has his own little way of

thinking about the under sides of things - it all comes in

handy too, it gives you the pas, say what you like.

That birthday suit there is painted with science. it is

organically correct, you can ex-amine it under the

microscope. You can see not only the horny and mucous strata

of the epidermis, but I've suggested the texture of the

corium underneath, with the oil- and sweat-glands, the

blood-vessels and tubercles - and then under that still the

layer of fat, the upholstering, you know, full of oil ducts,

the underpinning of the lovely female form. What is in your

mind as you work runs into your hand and has its influence -

it isn't really there, and yet somehow or other it is, and

that is what gives the lifelike

effect."

All

this was fuel to Hans Castorp's fire. His brow was flushed,

his eyes fairly sparkled, he had so much to say he knew not

where to begin. In the first place, he had it in mind to

remove the picture of Frau Chauchat from the window wall,

where it hung somewhat in shadow, and place it to better

advantage; next, he was eager to take up the Hofrat's

remarks about the constitution of the skin, which had keenly

interested him; and finally, he wanted to make some remarks

of his own, of a general and philosophical nature. which

interested him no less

mightily.

Laying

his hands upon the painting to unhook it, he eagerly be-gan:

"Yes, yes indeed, that is all very important. What I'd like

to say is - I mean, you said, Herr Hofrat, if I understood

rightly, you said: 'In another relation.' You said it was

good when there was some other relation besides the lyric -

I think that was the word you used - the artistic, that is;

In short, when one looked at the thing from another point of

view - the medical, for example. That's all so enormously to

the point, you know -I do beg your pardon, Herr Hofrat, but

what I mean is that it is so exactly and precisely right,

because after all it is not a question of any funda-mentally

different relations or points of view, but at bottom just

variations of one and the same, just shadings of it, so to

speak, I mean: variations of one and the same universal

interest, the artistic impulse itself being a part and a

manifestation of it too, if I may say so. Yes, if you will

pardon me, I will take down this picture, there s postively

no light here where it hangs, permit me to carry it over to

the sofa, we shall see if it won't look entirely - what I

meant to

/

Page 260 /

say

was: what is the main concern of the study of medicine? I

know nothing about it, of course - but after all isn't its

main con-cern with human beings? And jurisprudence - making

laws, pro- nouncing judgment - its main concern is with

human beings too. And philology, which is nearly always

bound up with the profes- sion of pedagogy? And theology,

with the care of souls, the office of spiritual shepherd?

All of them have to do with human beings, all of them are

degrees of one and the same important, the same fundamental

interest, the interest in humanity. In other words, they are

the humanistic callings, and if you go in for them you have

to study the ancient languages by way of foundation, for the

sake of formal training, as they say. Perhaps you are

surprised at my talk-ing about them like that, being only a

practical man and on the technical side. But I have been

thinking about these questions lately, m the rest-cure; and

I find it wonderful, I find it a simply priceless

arrangement of things, that the formal, the idea of form, of

beautiful form, lies at the bottom of every sort of

humanistic calling. It gives it such nobility, I think, such

a sort of disinterested- ness, and feeling, too, and - and -

courtliness - it makes a kind of chivalrous adventure out of

it. That is to say - I suppose I am ex-pressing myself very

ridiculously, but - you can see how the things of the mind

and the love of beauty come together, and that they always

really have been one and the same - in other words, science

and art; and that the calling of being an artist surely

belongs with the others, as a sort of fifth faculty, because

it too is a humanistic calling, a variety of humanistic

interest, in so far as its most im-portant theme or concern

is with man - you will agree with me on that point. When I

experimented in that line in my youth, I never painted

anything but ships and water, of course. But

notwithstanding, in my eyes the most interesting branch of

painting is and remains portraiture, because it has man for

its immediate object- that was why I asked at once if you

had done anything in that field. - Wouldn't this be a far

more favourable place for it to hang?

"

Both

of them, Behrens no less than Joachim, looked at him amazed

- was he not ashamed of this confused, impromptu ha- rangue?

But no, Hans Castorp was far too preoccupied to feel self-

conscious. He held the painting against the sofa wall, and

demanded to know if it did not get a much better light. Just

then the servant brought a tray, with hot water, a

spirit-lamp, and coffee-cups.

Behrens

motioned them into the cabinet, saying: " Then you must have

been more interested in sculpture, originally, than in

painting, I should think. Yes, of course, it gets more light

there; if you think it can stand it. I should suppose so,

because sculpture

/

Page 261 /

concerns

itself more purely and exclusively with the human form. But

we mustn't let the water boil

away."

"

Quite right, sculpture, " Hans Castorp said, as they went.

He forgot either to hang up or put down the picture he had

been hold- ing, but tugged it with him into the neighbouring

room. " Cer- tainly a Greek Venus or athlete is more

humanistic, it is probably at bottom the most humanistic of

all the arts, when one comes to think about

it!"

"

Well, as far as little Chauchat goes, she is a better

subject for painting than sculpture. Phidias, or that other

chap with the Mo- saic ending to his name, would have stuck

up their noses at her style of physiognomy. - Hullo, where

are you going with the ham?"

"

Pardon me, I'll just lean it here against the leg of my

chair, that will do very well for the moment. The Greek

sculptors did not trouble themselves about the head and

face, their interest was more with the body, I suppose that

was their humanism.-And the plasticity of the female form -

so that is fat, is it? "

"

That is fat," the Hofrat said concisely. He had opened a

hang-ing cabinet, and taken thence the requisites for his

coffee-making: a cylindrical Turkish mill, a long-handled

pot, a double receptacle for sugar and ground coffee, all in

brass. " Palmitin, stearin, olein," he went on, shaking the

coffee berries from a tin box into the mill, which he began

to turn. " You see I make it all myself, it tastes twice as

good. - Did you think it was ambrosia?

"

"

No, of course I knew. Only it sounds strange to hear it like

that," Hans Castorp said.

They

were seated in the comer between door and window, at a

bamboo tabouret which held an oriental brass tray, upon

which Behrens had set the coffee-machine, among the smoking

utensils. Joachim was next Behrens on the ottoman,

overflowing with cush- ions; Hans Castorp sat in a leather

arm-chair on castors, against which he had leaned Frau

Chauchat's picture. A gaily-coloured carpet was beneath

their feet. The Hofrat ladled coffee and sugar into the

long-handled pot, added water, and let the brew boil up over

the flame of the lamp. It foamed brownly in the little

onion- pattern cups, and proved on tasting both strong and

sweet.

"

Your own as well," Behrens said. " Your' plasticity' - so

far as you have any - is fat too, though of course not to

the same ex-tent as with a woman. With us fat is only about

five per cent of the body weight, in females it is one

sixteenth of the whole. Without that subcutaneous cell

structure of ours, we should all be nothing but fungoid

growths. It disappears, with time, and then come the

unaesthetic wrinkles in the drapery. The layer is thickest

on the fe-

/

Page 262 /

male

breast and belly, on the front of the thighs, everywhere, in

short, where there is a little something for heart and hand

to take hold of. The soles of the feet are fat and

ticklish."

Hans

Castorp turned the cylindrical coffee-mill about in his

hands. It was, like the rest of the set, Indian or Persian

rather than Turkish; the style of the engraving showed that,

with the bright surface of the pattern standing out against

the purposely dulled background. He looked at the design,

without immediately seeing what it was. When he did, he

blushed unawares.

"

Yes, that is a set for single gentlemen, " Behrens said. " I

keep it locked up, you see, my kitchen queen might hurt her

eyes looking at it. It won't do you gentlemen any harm, I

take it. It was given to me by a patient, an Egyptian

princess who once honoured us with a year or so of her

presence. You see, the pattern repeats itself on the whole

set. Pretty roguish, what? "

"

Yes, it is quite unusual, " Hans Castorp answered. " Ha ha!

No, it doesn't trouble me. But one can take it perfectly

seriously;

solemnly,

in fact - only then it is rather out of place on a

coffee-machine. The ancients are said to have used such

motifs on their sarcophagi. The sacred and the obscene were

more or less the same thing to

them."

"

I should say the princess was more for the second," Behrens

said. " Anyhow she still sends me the most wonderful

cigarettes, superfinissimos, you know, only sported on

first-class occasions." He fetched the garish-coloured box

from the cupboard and offered them. Joachim drew his heels

together as he received his cigarette. Hans Castorp helped

himself to his; it was unusually large and thick, and had a

gilt sphinx on it. He began to smoke - it was won-derful, as

Behrens had said.

"

Tell us some more about the skin," he begged the Hofrat; "

that is, if you will be so kind." He had taken Frau

Chauchat's portrait on his knee, and was gazing at it,

leaning back in his chair, the cigarette between his lips.

Not about the fat-layer, we know about that now. About the

human skin in general, that you know so well how to paint.

"

"

About the skin. You are interested in physiology?

"

"

Very much. Yes, I've always felt a good deal of interest in

it. The human body - yes, I've always had an uncommon turn

for it. I'vc sometimes asked myself whether I ought not to

have been a physician - it would.n't have been a bad idea,.

in a way: Because if you are interested in the body, you

must be interested m disease - specially interested, isn't

that so? But it doesn't signify, I might have been such a

lot of things - for example, a clergyman."/ Page 263

/ Indeed?

"

"

Yes, I've sometimes had the idea I should have been

decidedly in my element there."

"

How did you come to be an engineer, then?

"

"

I Just happened to - it was more or less outward

circumstances that decided the

matter."

"Well,

about the skin. What do you want to hear about your sensory

sheath? You know, don't you, that it is your outside brain -

ontogenetically the same as that apparatus of the so-called

higher centres up there in your cranium? The central nervous

system is nothing but a modification of the outer

skin-layer; among the lower animals the distinction between

central and peripheral doesn't exist, they smell and taste

with their skin, it is the only sensory organ they have.

Must be rather nice - if you can put yourself in their

place. On the other hand, in such highly differen-tiated

forms of life as you and I are, the skin has fallen from its

high estate; it has to confine itself to feeling ticklish;

that is to say, to being simply a protective and registering

apparatus - but devil-ishly on the qui vive for anything

that tries to come too close about the body. It even puts

out feelers - the body hairs, which are noth-ing but

hardened skin cells - and they get wind of the approach of

whatever it is, before the skin itself is touched. Just

between our- selves, it is quite possible that this

protecting and defending func- tion of the skin extends

beyond the physical. Do you know what makes you go red and

pale? "

"

Not very precisely."

"

Well, neither do we, ' very precisely,' to be frank - at

least, as far as blushing is concerned. The situation is not

quite clear; for the dilatory muscles which are presumably

set in action by the vaso- motor nerves haven't yet been

demonstrated in relation to the blood-vessels. How the cock

really swells his comb, or any of the other well-known

instances come about, is still a mystery, par- ticularly

where it is a question of emotional influences in play. We

assume that a connexion subsists between the outer rind of

the cerebrum and the vascular centre in the medulla. Certain

stimuli - for instance, let us say, like your being

powerfully embarrassed, set up the connexion, and the nerves

that control the blood-vessels function toward the face, and

they expand and fill, and you get a face like a turkey-cock,

all swelled up with blood so you can't see out of your eyes.

On the other hand, suppose you are in suspense, something is

going to happen - it may be something tremendously

beautiful, for aught I care - the blood-vessels that feed

the skin contract, it gets pale and cold and sunken, you

look like a dead

/

Page 264 /

man,

with big, lead-coloured eye-sockets and a peaked nose. But

the Sympathicus makes your heart thump away like a

good fellow."

"So

that is how it happens," Hans Castorp

said.

"

Something like that. Those are reactions, you know. But it

is the nature of reactions and reflexes to have a reason for

happening; we are beginning to suspect, we physiologists,

that the phenomena accompanying emotion are really defence

mechanisms, protective reflexes of the system. Goose-flesh,

now. Do you know how you come to have goose-flesh? ""Not

very clearly either, I'm

afraid."

"

That is a little contrivance of the sebaceous glands, which

se- crete the fatty, albuminous substance that oils your

skin and keeps it supple, and pleasant to feel of. Not very

appetizing, maybe, but without it the skin would be all

withered and cracked. Without the cholesterin, it is hard to

imagine touching the human skin at all. These sebaceous

glands have little erector-muscles that act upon them, and

when they do so, then you are like the lad when the princess

poured the pail of minnows over him. Your skin gets like a

file, and if the stimulus is very powerful, the hair ducts

are erected too, the hair on your head bristles up and the

little hairs on your body, like quills upon the fretful

porcupine - and you can say, like the youth in the story,

that now you know how to shiver and

shake."

"Oh,"

said Hans Castorp, " I know how already. I shiver rather

easily, on all sorts of provocation. Only what surprises me

is that the glands are erected for such different reasons.

It gives one goose-flesh to hear a slate-pencil run across a

pane of glass; but when you hear particularly beautiful

music you suddenly find you have it too, and when I was

confirmed and took my first communion, I had one shiver

after another, it seemed as though the prickling and

stickling would never leave off. Imagine those little

muscles acting for such different reasons!

"

Oh,"

Behrens said, " tickling's tickling. The body doesn't give a

hang for the content of the stimulus. It may be minnows, it

may be the Holy Ghost, the sebaceous glands are erected just

the same."

Hans

Castorp regarded the picture on his

knee.

"

Herr Hofrat," he said, " I wanted to come back to something

you said a moment ago, about internal processes, lymphatic

action, and that sort of thing. Tell us about it -

particularly about the lymphatic system, it interests me

tremendously "

"I

believe you," Behrens responded. " The lymph is the most

refined, the most rarefied, the most intimate of the body

juices. I dare say you had an inkling of the fact in your

mind ", when you

/

Page 265 /

asked.

People talk about the blood, and the mysteries of its com-

position, and what an extraordinary fluid it is. But it is

the lymph that is the juice of juices, the very essence, you

understand, ichor, blood-milk, creme de la creme; as

a matter of fact, after a fatty diet it does look like

milk." And he went on, in his lively and whimsical

phraseology, to gratify Hans Castorp's desire. And first he

characterized the blood, a serum composed of fat, albumen,

iron, sugar and salt, crimson as an opera-cloak, the product

of respira- tion and digestion, saturated with gases, laden

with waste products, which was pumped at 98.4° of heat

from the heart through the blood-vessels, and kept up

metabolism and animal warmth through- out the body - in

other words, sweet life itself. But, he said, the blood did

not come into immediate contact with the body cells. What

happened was that the pressure at which it was pumped caused

a milky extract of it to sweat through the walls of the

blood- vessels, and so into the tissues, so that it filled

every tiny interstice and cranny, and caused the elastic

cell-tissue to distend. This dis- tension of the tissues, or

turgor, pressed the lymph, after it had nicely swilled out

the cells and exchanged matter with them, into the vasa

lymphatica, the lymphatic vessels, and so back into the

blood again, at the rate of a litre and a half a day. He

went on to speak of the lymphatic tubes and absorbent

vessels; described the secretion of the breast milk, which

collected lymph from legs, abdomen, and breast, one arm, and

one side of the head; described the very delicately

constructed filters called lymphatic glands which were

placed at certain points in the lymphatic system, in the

neck, the arm-pit, and the elbow-joint, the hollow under the

knee, and other soft and intimate parts of the

body.

"

Swellings may occur in these places," Behrens explained.

In-durations of the lymphatic glands, let us say, in the

knee-pan or the arm-joint, dropsical tumours here and there,

and we base our diag- nosis on them - they always have a

reason, though not always a very pretty one. Under such

circumstances there is more than a suspicion of tubercular

congestion of the lymphatic

vessels."

Hans

Castorp was silent a little

space.

"

Yes," he said, then, in a low voice, " it is true, I might

very well have been a doctor. The flow of the breast milk -

the lymph of the legs - all that interests me very, very

much. What is the body? " he rhapsodically burst forth. What

is the flesh? What is the physical being of man? What is he

made of? Tell us this after- noon, Herr Hofrat, tell us

exactly, and once and for all, so that we mar know!" " Of

water," answered Behrens. " So you are interested in or-

/

Page 266 /

ganic

chemistry too? The human body consists, much the larger part

of it, of water. No more and no less than water, and nothing

to get wrought up about. The solid parts are only

twenty-five per cent of the whole, and of that twenty are

ordinary white of egg, protein, if you want to use a

handsomer word. Besides that, a little fat and a little

salt, that's about all."

"

But the white of egg - what is that?

"

"

Various primary substances: carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, oxy-

gen, sulphur. Sometimes phosphorus. Your scientific

curiosity is running away with itself. Some albumens are in

composition with carbo-hydrates; that is to say, grape-sugar

and starch. In old age the flesh becomes tough, that is

because the collagen increases in the connective tissue -

the lime, you know, the most important constituent of the

bones and cartilage. What else shall I tell you? In the

muscle plasma we have an albumen called fibrin; when death

occurs, it coagulates in the muscular tissue, and causes the

rigor mortis."

"

Right-oh, I see, the rigor mortis," Hans Castorp said

blithely.

"

Very good, very good. And then comes the general analysis-

the anatomy of the grave."

"

Yes, of course. But how well you put it! Yes, the movement

becomes general, you flow away, so to speak - remember all

that water! The remaining constituents are very unstable;

without life, they are resolved by putrefaction into simpler

combinations, anor- ganic."

"

Dissolution, putrefaction," said Hans Castorp. "They are the

same thing as combustion: combination with oxygen - am I

right? "

"

To a T. Oxidization."

"

And life? "

"

Oxidization too. The same. Yes, young man, life too is prin-

cipally oxidization of the cellular albumen, which gives us

that beautiful animal warmth, of which we sometimes have

more than we need. Tut, living consists in dying, no use

mincing the matter- une destruction organique,

as some Frenchman with his native levity has called it. It

smells like that, too. If we don't think so, our judgment is

corrupted."

"

And if one is interested in life, one must be particularly

in- terested in death, mustn't one?

"

"

Oh, well, after all, there is some sort of difference. Life

is life which keeps the form through change of

substance."

"

Why should the form remain? " said Hans

Castorp

/

Page 267 /

Why?

Young man, what you are saying now sounds far from

humanistic."

"

Form is folderol."

"

Well, you are certainly in great form to-day - you're regu-

larly kicking over the traces. But I must drop out now,"

said the Hofrat. " I am beginning to feel melancholy," and

he laid his huge hand over his eyes. " I can feel it coming

on. You see, I've drunk coffee with you, and it tasted good

to me, and all of a sudden it comes over me that I am going

to be melancholy. You gentlemen must excuse me. It was an

extra occasion, I enjoyed it no end -

"

The

cousins had sprung up. They reproached themselves for having

taxed the Hofrat's patience so long. He made proper

pro-test. Hans Castorp hastened to carry Frau Chauchat's

portrait into the next room and hang it once more on the

wall. They did not need to re-traverse the garden to arrive

at their own quarters; Behrens directed them through the

building, and accompanied them to the dividing glass door.

In the mood that had come over him so unexpectedly, his

goggling eyes blinked, and the bone of his neck stuck out,

both more than ever; his upper lip, with the clipped,

one-sided moustache, had taken on a querulous

expression.

As

they went along the corridors Hans Castorp said to his

cousin: . " Confess that it was a good idea of

mine."

"

It was a change,at least," responded Joachim. .. And you

cer- tainly took occasion to air your views on a good many

subjects. It was a bit complicated for me. It is high time

now that we went in to the rest-cure, we shall have at least

twenty minutes before tea. You probably think it is folderol

to pay so much attention to it, now you've taken to kicking

over the traces. But you don't need it so much as I do,

after all. "

|