THE MAGIC MOUNTAIN

Thomas Mann 1924

Research

AND

now came on, as come it must, what Hans Castorp had never

thought to experience: the winter of the place, the winter

of these high altitudes. Joachim knew it already: it had

been in full blast when he arrived the year before - but

Hans Castorp rather dreaded it, however well he felt himself

equipped. Joachim sought to reassure

him.

"

You must not imagine it grimmer than it is," he said, " not

really arctic. You will feel the cold less on account of the

dryness of the air and the absence of wind. It's the thing

about the change of temperature above the fog line; they've

found out lately that it

/

Page 268 /

gets

warmer in the upper reaches, something they did not know be-

fore. I should say it is actually colder when it rains. But

you have your sleeping-bag, and they turn on the heat when

they absolutely must."

And

in fact there could be no talk of violence or surprises; the

winter came mildly on, at first no different from many a day

they had seen in the height of summer. The wind had been two

days in the south, the sun bore down, the valIey seemed

shrunken, the side walls at its mouth looked near and bald.

Douds came up, behind Piz Michel and Tinzenhorn. and drove

north-eastwards. It rained heavily. Then the rain turned

foul, a whitish-grey, mingled with snow-flakes - soon it was

all snow, the vaIley was full of flurry; it kept on and on,

the temperature fell appreciably, so that the fallen snow

could not quite melt, but lay covering the valley with a wet

and threadbare white garment, against which showed black the

pines on the slopes. In the dining-room the radiators were

luke- warm. That was at the beginning of November - All

Souls'- and there was no novelty about it. In August it had

been even so; they had long left off regarding snow as a

prerogative of winter. White traces lingered after every

storm in the crannies of the rocky Rhatikon, the chain that

seemed to guard the end of the vaIley, and the distant

monarchs to the south were aIways in snow. But the storm and

the fall in the temperature both continued. A pale grey sky

hung low over the valley; it seemed to dissolve in flakes

and faIl soundlessly and ceaselessly, until one almost felt

un- easy. It turned colder by the hour. A morning came when

the ther- mometer in Hans Castorp's room registered

44°, the next morning it was only 40°. That was

cold. It kept within bounds, but it per- sisted. It had

frozen at night; now it froze in the day-time as well, and

all day long; and it snowed, with brief intervaIs, through

the fourth, the fifth, and the seventh days. The snow

mounted apace, it became a nuisance. Paths had been

shovelled as far as the bench by the watercourse, and on the

drive down to the valley; but these were so narrow that you

could only walk single file, and if you met anyone, you must

step off the pavement and at once sink knee- deep in snow. A

stone-roller drawn by a horse, with a man at his haIter,

rolled all day long up and down the streetS of the cure,

while a yellow diligence on runners, looking like an

old-fashioned post-coach, plied between village and cure,

with a snow-plough attached in front, shovelling the white

masses aside. The \vorld, this narrow, lofty, isolated world

up here, looked now well wadded and uphol-stered indeed: no

pillar or post but wore its white cap; the steps up to the

entrance of the Berghof had turned into an inclined

/

Page 269 /

plane;

heavy cushions, in the drollest shapes, weighed down the

branches of the Scotch firs - now and then one slid off and

raised up a cloud of powdery white dust in its fall. Round

about, the heights lay smothered in snow; their lower

regions rugged with the evergreen growth, their upper parts,

beyond the timber line, softly covered up to their

many-shaped summits. The air was dark, the sun but a pallid

apparition behind a veil. Yet a mild reflected bright- ness

came from the snow, a milky gleam whose light became both

landscape and human beings, even though these latter did

show red noses under their white or gaily-coloured woollen

caps.

In

the dining-room the onset of winter - the "season " of the

region - was the subject of conversation at all seven

tables. Many tourists and sportsmen \vere said to have

arrived and taken up resi- dence at the hotels in the Dorf

and the Platz. The height of the piled-up snow was estimated

at two feet; its consistency was said to be ideal for

skiing. The bob-run, which led down from the north-western

slope of the Schatzalp into the valley, was zealously worked

on, it would be possible to open it in the next few days,

unless a thaw put out all calculations. Everyone looked

forward eagerly to the activities of these sound people down

below - to the sports and races, which it was forbidden to

attend, but which num- bers of the patients resolved to see,

by cutting the rest-cure and slipping out of the Berghof.

Hans Castorp heard of a new sport that had come from

Scandinavia, .. ski-joring ": it consisted in races in which

the panicipants were drawn by horses while standing in their

skis. It was to see this that so many of the patients had

re- solved to slip out. - There was talk too of

Christmas.

Christmas!

Hans Castorp had never once thought of it. To be sure, he

had blithely said, and written, that he must spend the win-

ter up here with Joachim, because of what the doctors had

dis- covered to be the state of his health. But now he was

startled to realize that Christmas would be included in the

programme - per- haps because (and yet not entirely because)

he had never spent the Chrismas season anywhere but in the

bosom of the family. Well, if he must he must; he would have

to put up with it. He was no longer a child; Joachim seemed

not to mind, or else to have ad- justed himself

uncomplainingly to the prospect; and, after all, he said to

himself, think of all the places and all the conditions in

which Christmas has been celebrated before

now!

Yet

it did seem to him rather premature to begin thinking about

Christrnas even before the Advent season, six weeks at least

before the holiday! True, such an interval was easily

overleaped by the guests in the dining-hall: it was a mental

process in which Hans

/

Page 270 /

Castorp

had already some facility, though he had not yet learned to

practise it in the grand style, as the older inhabitants

did. Christ-mas, like other holidays in the course of the

year, served them for a fulcrum, or a vaulting-pole, with

which to leap over empty inter- vening spaces. They all had

fever, their metabolism was acceler- ated, their bodily

processes accentuated, keyed up - all this per-haps

accounted for the wholesale way they could put time behind

them. It would not have greatly surprised him to hear them

dis- count the Christmas holiday as well, and go on at once

to speak of the New Year and Carnival. But no-so capricious

and unstable as this they were not, in the Berghof

dining-room. Christmas gave them pause, it gave them even

matter for concern and brain-rack- ing. It was customary to

present Hofrat Behrens with a gift on Christmas eve, for

which a collection was taken up among the guests - and this

gift was the subject of much deliberation. A meet-ing was

called. Last year, so the old inhabitants said, they had

given him a travelling-trunk; this time a new

operating-table had been considered, an easel, a fur coat, a

rocking-chair, an inlaid ivory stethoscope. Settembrini,

asked for suggestions, proposed that they give the Hofrat a

newly projected encyclopzdic work called The Sociology of

Suffering; but he found only one person to agree with him, a

book-dealer who sat at Hermine Kleefeld's table. In short,

no decision had been reached. There was difficulty about

coming to an agreement with the Russian guests; a divergence

of views arose. The Muscovites declared their preference for

making an independent gift. Frau Stohr went about for days

quite outraged on account of a loan of ten francs which she

inadvisedly laid out for Frau Iltis at the meeting, and

which the latter had " forgotten " to return. She " forgot "

it. The shades of meaning Frau Stohr con-trived to convey in

this word were many and varied, but one and all expressive

of an entire disbelief in Frau Iltis's lack of memory,

which, it appeared, had been proof against the hints and

proddings Frau Stohr freely admitted having administered.

Several times she declared she would resign herself make

Frau Iltis a present of the sum. " I'll pay for both of us,"

she said. "Then my skirts will be cleared " But in

the end she hit upon another p!an and communi-cated it to

her table-mates, to their great delight: she had the

"management" refund her the ten francs and insert it in Frau

Iltis's weekly bill. Thus was the reluctant debtor

outwitted, and at least this phase of the matter

settled.

It

had stopped snowing, the sky began to clear. The blue-grey

cloud-masses parted to admit glimpses of the sun, whose rays

gave a bluish cast to the scene. Then it grew altogether

fair; a bright

/

Page 271 /

hard

frost and settled winter splendour reigned in the middle of

November. The arch of the loggia framed a glorious panorama

of snow-powdered forest, softly filled passes and ravines,

white, sun- lit valleys, and radiant blue heavens above all.

In the evening, when the almost full moon appeared, the

world lay in enchanted splen-dour, marvellous. Crystal and

diamond it glittered far and wide, the forest stood up very

black and white, the quarter of the heavens where the moon

was not showed deeply dark, embroidered with stars. On the

flashing surface of the snow, shadows, so strong, so sharp

and clearly outlined that they seemed almost more real than

the objects themselves, fell from houses, trees, and

telegraph-poles. An hour or so after sunset there would be

some founeen degrees of frost. The world seemed spellbound

in icy purity, its earthly blemishes veiled; it lay fixed in

a deathlike, enchanted trance.

Hans

Castorp stopped until far into the night in his balcony

above the ensorcelled winter scene - much longer than

Joachim, who retired at ten or a little later. His excellent

chair, with the sectional mattress and the neck-roll, he

pulled close to the snow- cushioned balustrade; at his hand

was the white table with the lighted reading-lamp, a stack

of books, and a glass of creamy milk, the "evening milk"

which was brought to each of the guests' rooms at nine

o'clock. Hans Castorp put a dash of cognac in his, to make

it more palatable. Already he "had availed himself of all

his means of protection against the cold, the entire outfit:

lay en- sconced well up to his chest in the buttoned-up

sleeping-sack he had acquired in one of the well-furnished

shops in the Platz, with the two camel's-hair rugs folded

over it in accordance with the ritual. He wore his winter

suit, with a shon fur jacket atop, a woollen cap, felt

boots, and heavily lined gloves, which, however, could not

prevent the stiffening of his

fingers.

What

held him so late - often until midnight and beyond, long

after the " bad " Russian pair had left their loge - was

partly the magic of the winter night, into which, until

eleven, were woven the mounting strains of music from near

and far. But even more it was inertia and excitement, both

of these at once, and in combina-tion: bodily inertia, the

physical fatigue which hated any idea of moving; and mental

excitement, the busy preoccupation of his thoughts with

certain new and fascinating studies upon which the young man

had embarked, and which left his brain no rest. The weather

affected him, his organism was stimulated by the cold; he

ate enormously, attacking the mighty Berghof meals, where

the roast goose followed upon the roast beef, with the usual

Berghof appetite, which was always even larger in winter

than in summer.

/

Page 272 /

At

the same time he had a perpetual craving for sleep; in the

day-time, as well as on the moonlit evenings, he would drop

off over his books, and then, after a few minutes'

unconsciousness, betake himself again to research. Talk

fatigued him. He was more in-clined than had been his habit

to rapid, unrestrained, even reckless speech; but if he

talked with Joachim, as they went on their snowy walks, he

was liable to be overtaken by giddiness and trembling, would

feel dazed and tipsy, and the blood would mount to his head.

His curve had gone up since the oncoming of winter, and

Hofrat Behrens had let fall something about injections;

these were usually given in cases of obstinate high

temperature, and Joachim and at least two-thirds of the

guests had them. But he himself felt sure that the increase

in his bodily heat had to do with the mental activity and

excitation which kept him in his chair on the balcony until

deep into the glittering, frosty night. The reading which

held him so late suggested such an explanation to his

mind.

No

little reading was done, in the rest-halls and private

loggias of the International Sanatorium Berghof; largely,

however, by the new-comers and " short-timers," for the

patients of many months' or years' standing had long learned

to kill time without mental effort or means of distraction,

by dint of a certain inner virtuosity they came to possess.

They even considered it beginners' awkward-ness to glue

yourself to a book. It was enough to have one lying in your

lap or on your little table, in case of need. The collection

of the establishment was an amplification of the literature

found in a dentist's waiting-room - in many languages,

profusely illustrated, and offered free of charge. The

guests exchanged volumes from the loan-library down in the

Platz; now and again there would be a book for which

everybody scrambled, even the condescending old inhabitants

reaching out their hands with ill-concealed eager-ness. At

the moment it was a cheap paper-backed volume, intro-duced

by Herr Albin, and entitled The Art of

Seduction: a very literal translation from the

French, preserving even the syntax of that language, and

thus gaining in elegance and pungency of pres-entation. In

matter it was an exposition of the philosophy of sen-sual

passion, developed in a spirit of debonair and

man-of-the-worldly paganism. Frau Stohr had read it early,

and pronounced it simply ravishing. Frau Magnus, the same

who had lost her albu-men tolerance, agreed unreservedly.

Her husband the brewer pur- portc:d to have profited

personally by a perusal, but regretted that his wife should

have taken up that sort of thing, because such read-ing

spoiled the women and gave them immodest ideas. His remarks

not a little increased the circulation of the volume. Two

ladies of

/

Page 273 /

the

lower rest-hall, Frau Redisch, the wife of a Polish

industrial magnate, and Frau Hessenfeld, a widow from

Berlin, both of these new arrivals since October, claimed

the book at the same time, and a regrettable incident arose

after dinner, yes, more than regrettable, for there was a

violent scene, overheard by Hans Castorp, in his loggia

above. It ended in spasms of hysteria on the part of one of

the women - it might have been Frau Redisch, but equally

well it might have been Frau Hessenfeld - and she was borne

away be-side herself to her own room. The youth of the place

had got hold of the treatise before those of riper years;

studying it in part in groups, after supper, in their

various rooms. Hans Castorp himself saw the youth with the

finger-nail hand it to Franzchen Oberdank in the dining-room

- she was a new arrival and a light case, a flaxen- hrored

young thing whose mother had just brought her to the

sanatorium.

There

may have been exceptions; there may have been those who

employed the hours of the rest-cure with some serious in-

tellectual occupation, some conceivably profitable study,

either by way of keeping in touch with life in the lowlands,

or in order to give weight and depth to the passing hour,

that it might not be pure time and nothing else besides.

Perhaps here and there was one - not, of course, to mention

Herr Settembrini, with his zeal for eliminating human

suffering, or Joachim with his Russian primer - yes, there

might be one, or two, thus occupied; if not among the guests

in the dining-room, which seemed not very likely, then among

the bedridden and moribund. Hans Castorp inclined to

be-lieve it. He himself, after imbibing all that Ocem

Steamships had to offer him, had ordered certain books from

home, some of them bearing on his profession, and they had

arrived with his winter clothing: scientific engineering,

technique of ship-building, and the like. But these volumes

lay now neglected in favour of other text- books belonging

to quite a different field, an interest in which had seized

upon the young man: anatomy, physiology, biology, works in

German, French and English, sent up to the Berghof by the

book-dealer in the village, obviously because Hans Castorp

had ordered them, as was indeed the case. He had done so of

his own motion, without telling anyone, on a solitary walk

he took down to the Platz while Joachim was occupied with

the weekly weigh-ing or injection. His cousin was surprised

when he saw the books in Hans Castorp's hands. They were

expensive, as scientific works always are: the prices were

marked on the wrappers and inside the front covers. Joachim

asked why, if his cousin wanted to read such books, he had

not borrowed them of the Hofrat, who surely

/

Page 274 /

possessed

a well-chosen stock. The young man answered that it was

quite a different thing to read when the book was one's own;

for his part, he loved to mark them and underline passages

in pencil. Joachim could hear, hours on end, the noise made

by the paper- knife going through the uncut

leaves.

The

volumes were heavy, unhandy. Hans Castorp propped them

against his chest or stomach as he lay; they were heavy, but

he did not mind. Lying there, his mouth half open, he let

his eye glide down the learned page, upon which fell the

light from his red- shaded lamp, though he might have read,

if need were, by the bril- liance of the moonlight alone. He

read, following the lines down the page with his head, until

at the bottom his chin lay sunk upon his breast - and in

this position the reader would pause perhaps for reflection,

dozing a little or musing in half-slumber, before lifting

his eyes to the next page. He probed profoundly. While the

moon took its appointed way above the crystalline splendours

of the mountain valley, he read of organized matter, of the

proper-ties of protoplasm, that sensitive substance

maintaining Itself in extraordinary fluctuation between

building up and breaking down; of form developing out of

rudimentary, but always present, pri- mordia; read wIth

compelling interest of life, and it sacred, im- pure

mysteries.

What

was life? No one knew. It was undoubtedly aware of it-self,

so soon as it was life; but it did not know what it was.

Con- sciousness, as exhibited by susceptibility to stimulus,

was undoubt-edly, to a certain degree, present in the

lowest, most undeveloped stages of life; it was impossible

to fix the first appearance.of con-scious processes at any

point In the history of the mdividual or the race;

immpossible to make consciousness contingent upon, say, the

presence of a nervous system. The lowest animal forms had no

nervous systems, still less a cerebrum; yet no one would

venture to deny them the capacity for responding to stimuli.

One could sus-pend life; not merely particular sense-organs,

not only nervous reactions, but life itself. One could

temporarily suspend the irrita- bility to sensation of every

form of living matter in the plant as well as in the animal

kingdom; one could narcotize ova and sperma- tozoa with

chloroform, chloral hydrate, or morp!une. Conscious- ness,

then, was simply a function of matter organized into life; a

function that in higher manifestations turned upon its

avatar and became an effort to explore and explain the

pnenomenon it dis-played - a hopeful-hopeless project of

life to achieve self-knowl-edge, nature in recoil-and

vainly, in the event, since she cannot be resolved in

knowledge, nor life, when all is said, listen to

itself.

/

Page 275 /

What

was life? No one knew. No one knew the actual point whence

it sprang, where it kindled itself. Nothing in the domain of

life seemed uncausated, or insufficiently causated, from

that point on; but life itself seemed without antecedent. If

there was anything that might be said about it, it was this:

it must be so highly developed, structurally, that nothing

even distantly related to It was present in the inorganic

world. Between the protean amreba and the vertebrate the

difference was slight, unessential, as com- pared to that

between the simplest living organism and that nature which

did not even deserve to be called dead, because it was in-

organic. For death was only the-logical negation of life;

but be- tween life and inanimate nature yawned a gulf which

research strove in vain to bridge. They tried to close it

with hypotheses, which it swallowed down without becoming

any the less deep or broad. Seeking for a connecting link,

they had condescended to the preposterous assumption of

structureless living matter, unorgan-ized organisms, which

darted together of themselves in the albu-men solution, like

crystals in the mother-liquor; yet organic dif- ferentiation

still remained at once condition and expression of all life.

One could point to no form of life that did not owe its

exist- ence to procreation by parents. They had fished the

primeval slime out of toe depth of the sea, and great had

been the jubilation - but the end of it all had been shame

and confusion. For it turned out that they had mistaken a

precipitate of sulphate of lime for proto-plasm. But then,

to avoid giving pause before a miracle - for life that built

itself up out of, and fell in decay into, the same sort of

matter as inorganic nature; would have been, happening of

itself, miraculous - they were driven to believe in a

spontaneous genera-tion - that is, in the emergence of the

organic from the inorganic - which was just as much of a

miracle. Thus they went on, devis-ing intermediate stages

and transitions, assuming the existence of organisms which

stood lower down than any yet known, but them-selves had as

forerunners still more primitive efforts of nature to

achieve life: primitive forms of which no one would ever

catch sight, for they were all of less than microscopic

size, and previous to whose hypothetic existence the

synthesis of protein compounds must already have taken

place.

What

then was life? It was warmth, the warmth generated by a

form-preserving instability, a fever of matter, which

accom-panied the process of ceaseless decay and repair of

albumen mole-cules that were too impossibly complicated, too

impossibly ingen-ious in structure. It was the existence of

the actually impossible-to-exist, of a half-sweet,

half-painful balancing, or scarcely balancing,

/

Page 276 /

in

this restricted and feverish process of decay and renewal,

upon the point of existence. It was not matter and it was

not spirit, but something between the two, a phenomenon

conveyed by mat-ter, like the rainbow on the waterfall, and

like the flame. Yet why not material- it was sentient to the

point of desire and disgust, the shamelessness of matter

become sensible of itself. the inconti-nent form of being.

It was a secret and ardent stirring in the frozen chastity

of the universal; it was a stolen and voluptuous impurity of

sucking and secreting; an exhalation of carbonic acid gas

and ma-terial impurities of mysterious origin and

composition. It was a pul-lulation, an unfolding, a

form-building (made possible by the over-balancing of its

instability, yet controlled by the laws of growth inherent

within it), of something brewed out of water, albumen, salt

and fats, which was called flesh, and which became form,

beauty, a lofty image, and yet all the time the essence of

sensuality and desire. For this form and beauty were not

spirit-borne; nor, like the form and beauty of sculpture,

conveyed by a neutral and spirit-consumed substance, which

could in all purity make beauty perceptible to the senses.

Rather was it conveyed and shaped by the somehow awakened

voluptuousness of matter, of the organic. dying-living

substance itself, the reeking

flesh.

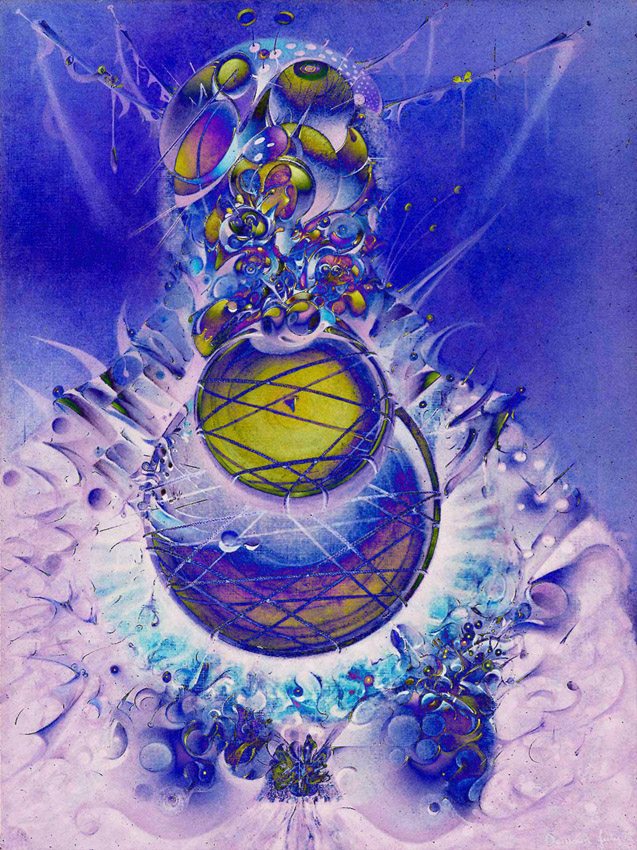

As

he lay there above the glittering valley, lapped in the

bodily warmth reserved to him by fur and wool, in the frosty

night illumined by the brilliance from a lifeless star, the

image of life displayed itself to young Hans Castorp. It

hovered before him, somewhere in space, remote from his

grasp, yet near his sense; this body, this opaquely whitish

form, giving out exhalations, moist, clammy; the skin with

all its blemishes and native impurities, with its spots,

pimples, discolorations, irregularities; its horny,

scalelike regions, covered over by soft streams and whorls

of rudimentary lanugo. It leaned there, set off against the

cold lifelessness of the inanimate world, in its own

vaporous sphere, relaxed, the head crowned with something

cool, horny, and pigmented, which was an outgrowth of its

skin; the hands clasped at the back of the neck. It looked

down at him beneath drooping lids, out of eyes made to

appear slanting by a racial variation in the lid-formation.

Its lips were half open, even a little curled. It rested its

weight on one leg, the hip-bone stood out sharply under the

flesh, while the other, relaxed, nestled its slightly bent

knee against the inside of the sup-porting leg, and poised

the foot only upon the toes. It leaned thus, turning to

smile, the gleaming elbows akimbo, in the paired sym-metty

of its limbs and trunk. The acrid. steaming shadows of the

arm-pits corresponded in a mystic triangle to the pubic

dark-

/

Page 277 /

ness,

just as the eyes did to the red, epithelial mouth-opening,

and the red blossoms of the breast to the navel lying

perpendicularly below. Under the impulsion of a central

organ and of the motor nerves originating in the spinal

marrow, chest and abdomen func- tioned, the peritoneal

cavity expanded and contracted, the breath, warmed and

moistened by the mucous membrane of the respira- tory canal,

saturated with secretions, streamed out between the lips,

after it had joined its oxygen to the haemoglobin of the

blood in the air-cells of the lungs. For Hans Castorp

understood that this living body, in the mysterious symmetry

of its blood-of its nourished structure, penetrated

throughout by nerves, veins, arteries, and capillaries; with

its inner framework of bones - marrow-filled tubular bones,

blade-bones, vertebrre - which with the addition of lime had

developed out of the original gelatinous tissue and grown

strong enough to support the body weight; with the cap-sules

and well-oiled cavities, ligaments and cartilages of its

joints, Its more than two hundred muscles, its central

organs that served for nutrition and respiration, for

registering and transmitting stimuli, its protective

membranes, serous cavities, its glands rich in secre-tions;

with the system of vessels and fissures of its highly

compli-cated interior surface, communicating through the

body-openings with the outer world - he understood that this

ego was a livmg unit of a very high order, remote indeed

from those very simple forms of life which breathed, took in

nourishment, even thought, with the entire surface of their

bodies. He knew it was built up out of myriads of such small

organisms, which had had their origin in a single one; which

had multiplied by recurrent division, adapted themselves to

the most varied uses, and functions, separated,

dif-ferentiated themselves, thrown out forms which were the

condition and result of their

growth.

This

body, then, which hovered before him, this individual and

living I, was a monstrous multiplicity of breathing and

self-nourishing individuals, which, through organic

conformation and adaptation to special ends, had parted to

such an extent with their essential individuality, their

freedom and living immediacy, had so much become anatomic

elements that the functions of some had become limited to

sensibility toward light, sound, contact, warmth; others

only understood how to change their shape or produce

di-gestive secretions through contraction; others, again,

were de-veloped and functional to no other end than

protection, support, the conveyance of the body juices, or

reproduction. There were modifications of this organic

plurality united to form the higher ego: cases where the

multitude of subordinate entities were only

/

Page 278 /

grouped

in a loose and doubtful way to form a higher living uait.

The student buried himself in the phenomenon of cell

colonies; he read about half-organisms, algae, whose single

cells, enveloped.. a mantle of gelatine, often lay apart

from one another, yet were multiple-cell formations, whIch,

if they had been asked, would not have known whether to be

rated as a settlement of single-celled individuals, or as an

individual single unit, and, in bearing witness, would have

vacillated quaintly between the I and the we. Nature here

presented a middle stage, between the highly social union of

countless elementary individuals to form the tissues and

organs of a superior I, and the free individual existence of

these simpler forms; the multiple-celled organism was only a

stage in the cyclic process, which was the course of life

itself, a periodic revolution from procreation to

procreation. The act of fructification, the sexual merging

of two cell-bodies, stood at the beginning of the upbuilding

of every rnultiple-celled individual, as it did at the

beginning of every row of generations of single elementary

forms,. and led back to itself. For this act was carried

through many species which had no need of it to multiply by

means of proliferation;until a moment came when the

non-sexually produced offspring found thcmselves once more

constrained to a renewal of the copu- lative function, and

the circle came full. Such was the multiple state of life,

sprung from the union of two parent cells, the asso- ciation

of many non-sexually originated generations of cell units;

its growth meant their increase, and the generative circle

came full again when sex-cells, specially developed elements

for the pur-pose of reproduction, had established themselves

and found the way to a new mingling that drove life on

afresh.

Our

young adventurer, supporting a volume of embryology on the

pit of his stomach, followed the development of the

or-ganism from the moment when the spermatozoon, first among

a host of its fellows, forced itself forward by a lashing

motion of its hinder part, struck with its forepart against

the gelatine mantle of the egg, and bored its way into the

mount of concep- tion, which the protoplasm of the outside

of the ovum arched agajnst its approach. There was no

conceivable trick or absurdity it would not have pleased

nature to commit by way of variation upon this fixed

procedure. In some animals, the male was a para-site in the

intestine of the female. In others, the male parent reached

with his arm down the gullet of the female to deposit the

semen within her; after which, bitten off and spat out, it

ran away by itself upon its fingers, to the confusion of

scientists, who for long had given it Greek and Latin names

an independent form

/

Page 279 /

of

life. Hans Castorp lent an ear to the learned strife between

ovists and animalculsts: the first of whom asserted that the

egg was in itself the complete little frog, dog, or human

being, the male element being only the incitement to its

growth; while the sec-ond saw in a spermatozoon, possessing

head, arms, and legs, the perfected form of life shadowed

forth, to which the egg performed only the office of "

nourisher in life's feast." In the end they agreed to

concede equal meritoriousness to ovum and semen, both of

which, after all sprang from originally indistinguishable

procre-ative cells. He saw the single-celled organism of the

fructified egg on the point of being transformed into a

multiple-celled organism, by striation and division; saw the

cell-bodies attach themselves to the lamellae of the mucous

membrane; saw the germinal vesicle, the blastula, close

itself in to form a cup or basin-shaped cavity, and begin

the functions of receiving and digesting food. That was the

gastrula, the protozoon, primeval form of all animal life,

pri-meval form of flesh-borne beauty. Its two epithelia, the

outer and the inner, the ectoderm and the entoderm, proved

to be prim:tive organs out of whose foldings-in and-out,

were developed the glands, the tissues, the sensory organs,

the body processes. A strip of the outer germinal layer, the

ectoderm, thickened, folded into a groove, closed itself

into a nerve canal, became a spinal column, became the

brain. And as the foetal slime condensed into fibrous

connective tissue, into cartilage, the colloidal cells

begirming to show gelatinous substance instead of mucin. he

saw in certain places the connective tissue take lime and

fat to itself out of the sera that washed it, and begin to

form bone. Embryonic man squatted in a stooping posture,

tailed, indistinguishable from em-bryonic pig; with enormous

abdomen and stumpy, formless extremities, the facial mask

bowed over the swollen paunch; the story of his growth

seemed a grim, unflattering science, like the cursory record

of a zoological family tree. For a while he had gill-pockets

like a roach. It seemed permissible, or rather unavoidable,

contemplating the various stages of development through

which he passed, to infer the very little humanistic aspect

presented by primitive man in his mature state. His skin was

furnished with twitching muscles to keep off insects; it was

thickly covered with hair; there was a tremendous

development of the mucous mem-brane of the olfactory organs;

his ears protruded, were movable, took a lively part in the

play of the features, and were much better adapted than ours

for catching sounds. His eyes were protected by a third,

nictating lid; they were placed sidewise, excepting the

third, of which the pineal gland was the rudimentary trace,

and

/

Page 280 /

which

was able, looking upwards, to guard him from dangers from

the upper air. Primitive man had a very long intestine, many

molars, and sound-pouches on the larnyx the better to roar

with, also he carried his sex-glands on the inside of the

intestinal cavity.

Anatomy

presented our investigator with charts of human limbs,

skinned and prepared for his inspection; he saw their

superficial and their buried muscles, sinews, and tendons:

those of the thighs, the foot, and especially of the arm,

the upper and the forearm. He learned the Latin names with

which medicine, that subdivision of the humanities, had

gallantly equipped them. He passed on to the skeleton, the

development of which presented new points of view - among

them a clear perception of the essential unity of all that

pertains to man, the correlation of all branches of

learning. For here, strangely enough, he found himself

reminded of his own field - or shall we say his former

field? - the scientific calling which he had announced

himself as having embraced, introducing himself thus to Dr.

Krokowski and Herr Settembrini on his ar- rival up here. In

order to learn something - it had not much mat-tered what -

he had learned in his technical school about statics, about

supports capable of flexion, about loads, about construction

as the advantageous utilization of mechanical material. It

would of course be childish to think that the science of

engineering, the rules of mechanics, had found application

to organic nature; but just as little might one say that

they had been derived from organic nature. It was simply

that the mechanical laws found themselves repeated and

corroborated in nature. The principle of the hollow cylinder

was illustrated in the structure of the tubular bones, in

such a way that the static demands were satis-fied with the

precise minimum of solid structure. Hans Castorp had learned

that a body which is put together out of staves and bands of

mechanically utilizable matter, conformably to the de- mands

made by draught and pressure upon it, can withstand the same

weight as a solid column of the same material. Thus in the

development of the tubular bones, it was comprehensible

that, step for step with the formation of the solid

exterior, the inner parts, which were mechanically

superfluous, changed to a fatty tissue, the marrow. The

thigh-bone was a crane, in the construction of which organic

nature, by the direction she had given the shaft, carried

out, to a hair, the same draught- and pressure-curves which

Hans Castorp had had to plot in drawing an instrument

serving a similar purpose. He contemplated this fact with

pleasure; he en- joyed the reflection that his relation to

the femur, or to organic

/

Page 281 /

nature

generally was now threefold: it was lyrical, it was medical,

it was technological; and all of these, he felt, were one in

being human, they were variations of one and the same

pressing human concern, they were schools of humanistic

thought.

But

with all this the achievements of the protoplasm remained

unaccountable: it seemed forbidden to life that it should

under-stand itself. Most of the bio-chemical processes were

not only unknown, it lay in their very nature that they

should escape at-tention. Almost nothing was known of the

structure or composi-tion of the living unit called the "

cell." What use was there in establishing, the components of

lifeless muscle, when the living did not let itself be

chemically examined? The changes that took place when the

rigor mortis set in were enough to make worthless all

investigation. Nobody understood metaboIism, nobody under-

stood the true inwardness of the functioning of the nervous

sys- tem. To what properties did the taste corpuscles owe

their reaction? In what consisted the various kinds of

excitation of cer- tain sensory nerves by odour-possessing

substances? In what, in- deed, the property of smell itself?

The specific odours of man and beast consisted in the

vaporization of certain unknown substances. The composition

of the secretion called sweat was little under- stood. The

glands that secreted it produced aromata which among mammals

undoubtedly played an imporant role, but whose sig-nificance

for the human species we were not in a position to ex-

plain. The physiological significance of imponant regions of

the body was shrouded in darkness. No need to mention the

vermi- form appendix, which was a mystery; in rabbits it was

regularly found full of a pulpy substance, of which there

was nothing to say as to how it got in or renewed itself.

But what about the white and grey substance which composed

the medulla, what of the optic thalamus and the grey inlay

of the pons Varolii? The sub-stance composing the

brain and marrow was so subject to dis- integration, there

was no hope whatever of determining its struc-ture. What was

it relieved thie cortex of activity during slumber? What

prevented the stomach from digesting itself - as sometimes,

in fact, did happen after death? One might answer, life: a

special power of resistance of the living protoplasm; but

this would be not to recognize the mystical character of

such an explanation. The theory of such an everyday

phenomenon as fever was full of contradictions. Heightened

oxIdization resulted in increased warmth, but why was there

not an increased expenditure of warmtth to correspond? Did

the paralysis of the sweat-secretions depend upon

contraction of the skin? But such contraction took

/

Page 282 /

place

only in the case of " chills and fever," for otherwise, in

fever, the skin was more likely to be hot. Prickly heat

indicated the centnl nervous system as the seat of the

causes of heightened catabolism as well as the source of

that condition of the skin which we were content to call

abnormal, because we did not know how to define

it.

But

what was all this ignorance, compared with our utter

help-lessness in the presence of such a phenomenon as

memory, or of that other more prolonged and astounding

memory which we called the inheritance of acquired

characteristics? Out of the question to get even a glimpse

of any mechanical possibility of explication of such

performances on the part of the cell-substance. The

spermatozoon that conveyed to the egg countless complicated

individual and racial characteristics of the father was

visible only through a microscope; even the most powerful

magnification was not enough to show it as other than a

homogeneous body, or to determine its origin; it looked the

same in one animal as in another. These factors forced one

to the assumption that the cell was in the same case as with

the higher form it went to build up: that it too was already

a higher form, composed in its turn by the division of

living bodies, individual living units. Thus one passed from

the supposed smallest unit to a still smaller one; one was

driven to separate the elementary into its elements. No

doubt at all but just as the animal kingdom was composed of

various species of animals, as the human-animal organism was

composed of a whole animal kingdom of cell species, so the

cell organism was composed of a new and varied animal

kingdom of elementary units, far below microscopic size,

which grew spontaneously, increased spontaneously according

to the law that each could bring forth only after its kind,

and, acting on the principle of a division of labour, served

together the next higher order of

existence.

Those

were the genes, the living germs, bioblasts, biophores-lying

there in the frosty night, Hans Castorp rejoiced to make

acquaintance with them by name. Yet how, he asked himself

ex-citedly, even after more light on the subject was

forthcoming. how could their elementary nature be

established? If they were living. they must be organic,

since life depended upon organiza-tion. But if they were

organized, then they could not be ele-mentary. since an

organism is not single but multiple. They were units within

the organic unit of the cell they built up. But if they

were, then, however impossibly small they were. they must

them-selves be built up. organically built up. as a law of

their existence; for the conception of a living unit meant

by definition that it was

/

Page 283 /

built

up out of smaller units which were subordinate; that is,

organized with reference to, a higher form. As long as

division yielded organIc unIts possessing the propertIes of

life - asslmila-tion and reproduction - no limits were set

to it. As long as one spoke of living units, one could not

correctly speak of elementary units, for the concept of

unity carried with it in perpetuity the concept of

subordinated, upbuilding unity; and there was no such thing

as elementary life, in the sense of something that was

already life, and yet elementary. And still, though without

logical existence, something of the kind must be eventually

the case; for it was not possible. to brush aside like that

the idea of the original procreation, the rise of life ; out

of what was not life. That gap which in exterior nature we

vainly sought to close, that between living and dead matter,

had its counterpart in nature's organic existence, and must

somehow either be closed up or bridged over. Soon or late,

division must yield " units " which, even though in

composition, were not organ- ized, and which mediated

betWeen life and absence of life; molec- ular groups, which

represented the transition between vitalized organization

and mere chemistry. But then, arrived at the mole-cule, one

stood on the brink of another abyss, which yawned yet more

mysteriously than that between organic and inorganic

na-ture: the gulf between the material and the immaterial.

For the molecule was composed of atoms, and the atom was

nowhere near large enough eveh to be spoken of as

extraordinarily small. It was so small, such a tiny, early,

transitional mass, a coagulation of the unsubstantial, of

the not-yet-substantial and yet substance-like, of energy,

that it was scarcely possible yet - or, if it had been, was

now no longer possible - to think of it as material, but

rather as mean and border-line between material and

immaterial. The prob- lem of another original procreation

arose, far more wild and mys- terious than the organic: the

primeval birth of matter out of the immaterial. In fact the

abyss between material and. immaterial yawned as widely,

pressed as importunately - yes, more impor-tunately - to be

closed, as that between organic and inorganic -nature. There

must be a chemistry of the immaterial, there must be

combinations of the insubstantial, out of which sprang the

material - the atoms might represent protozoa of material,

by their nature substance and still not yet qulte substance.

Yet arrived at the .. not even small," the measure slipped

out of the hands; for " not even small " meant much the same

as enormously large "; and the step to the atom provecl: to

be without exaggeration portentous in the highest degree.

For at the very moment when one had assisted at

/

Page 284 /

the

final division of matter, when one had divided it into the

im-possibly small, at that moment there suddenly appeared

upon the horizon the astronomical

cosmos!

The

atom was a cosmic system, laden with energy; in which

heavenly bodies rioted rotating about a centre like a sun;

through whose ethereal space comets drove with the speed of

light years. kept in their eccentric orbits by the power of

the central body. And that was as little a mere comparison

as it would be were one to call the body of any

multiple-celled organism a " cell state." The city, the

state, the social community regulated according to the

principle of division of labour, not only might be compared

to organic life, it actually reproduced its conditions. Thus

in the in-most recesses of nature, as in an endless

succession of mirrors. was reflected the macrocosm of the

heavens, whose clusters, throngs. groups. and figures, paled

by the brilliant moon, hung over the dawing, frost-bound

valley, above the head of our muffled adept. Was it too bold

a thought that among the planets of the atomic solar system

- those myriads and milky ways of solar systems which

constituted matter - one or other of these inner-worldly

heavenly bodies might find itself in a condition

corresponding to that which made it possible for our earth

to become the abode of life? For a young man already rather

befuddled inwardly. suffering from abnormal skin-conditions.

who was not without all and any experience in the realm of

the illicit, it was a specularion which, far from being

absurd, appeared so obvious as to leap to the eyes, highly

evident, and bearing the stamp of logical truth. The "

small- ness " of these inner-worldly heavenly bodies would

have been an objection irrelevant to the hypothesis; since

the conception of large or small had ceased to be pertInent

at tlle moment when the cosmic character of the "smallest"

particle of matter had been revealed; while at the same

time, the conceptions of " outside " and " inside " had also

been shaken. The atom-world was an " outside." as, very

probably, the earthly star on which we dwelt was,

organically re-garded, deeply" inside." Had not a researcher

once, audaciously fanciful, referred to the" beasts of the

Milky Way," cosmic mon-sters whose flesh, bone, and brain

were built up out of solar sys- tems? But in that case, Hans

Castorp mused, then in the moment when one thought to have

come to to the end, it all began over again from the

beginning! For then, in the very innermost of his nature,

and in the inmost of that innermost, perhaps there was just

himself, just Hans Castorp, again and a hundred times Hans

Castorp, with burning face and stiffening fingers, lying

muffled on a balcony, with a view across the moonlit,

frost-nighted high valley. and prob-

/

Page 285

ing,

with an interest both humanistic and medical, into the life

of the body!

He

held a volume of pathological anatomy in the red ray from

his table-lamp, and conned its text and numerous

reproductions. He read of the existcnce of parasitic

cell-juncture and of infec- tious tumours. These were forms

of tissue - and very luxuriant forms too - produced by

foreign cell-bodies in an organism which had proved

receptive to them, and in some way or other - one must

probably say perversely - had offered them peculiarly

fa-vourable conditions.lt was not so much that the parasite

took away nourishment from the surrounding tissues, as that,

in the process of building up and breaking down which went

on in it as in every other cell, it produced organic

combinations which were extraor- dinarily toxic - undeniably

destructive - to the cells where it had been entenained.

They had found out how to isolate the toxin from a number of

micro-organisms and produce it in concentrated form; and it

was amazing to see what small doses of this substance, which

simply belonged to a group of protein combinations, could,

when introduced into the circulation of an animal, produce

symptoms of acute poisoning and rapid degeneration. The

outward sign of this inward decay was a growth of tissue,

the pathological tumour, which was the reaction of the cells

to the stimulus of the foreign bacilli. Tubercles developed,

the size of a millet-seed, composed of cells resembling

mucous membrane, among or within which the bacilli lodged;

some of these were extraordinarily rich in proto- plasm,

very large, and full of nuclei. However, all this good

living soon led to ruin; for the nuclei of these monster

cells began to break down, the protoplasm they contained to

be destroyed by coagulation, and further areas of tissue to

be involved. They were attacked by inflammation, the

neighbouring blood-vessels suffered by contagion. White

blood-corpuscles were attracted to the seat of the evil; the

breaking-down proceeded apace; and meanwhile the soluble

toxins released by the bacteria half already poisoned the

nerve-centres, the entire organization was in a state of

high fever, and staggered - so to speak with heaving bosom -

toward dissolu- tion.

Thus

far pathology, the theory of disease, the accentuation of

the physical through pain; yet, in so far as it was the

accentuation of the physical, at the same time accentuation

through desire. Dis- ease was a perverse, a dissolute form

of life. And life? Life itself? Was it perhaps only an

infection, a sickening of matter? Was that which one might

call the original procreation of matter only a disease, a

growth produced by morbid stimulation of the imma-

/

Page 286 /

terial?

The first step toward evil, toward desire and death, was

taken precisely then, when there took place that first

increase in the density of the spiritual, that

pathologically luxuriant morbid growth, produced by the

irritant of some unknown infiltration; this, in part

pleasurable, in part a motion of self-defence, was the

primeval stage of matter, the transition from the

insubstantial to the substance. This was the Fall. The

second creation. the birth of the organic out of the

inorganic, was only another fatal stage in the progress of

the corporeal toward consciousness, just as disease in the

organism was an intoxication. a heightening and unlicensed

accentuation of its physical state; and life, life was

nothing but next step on the reckless path of the spirit

dishonoured; nothing but the automatic blush of matte!'

roused to sensation and become receptive for that which

awaked it.

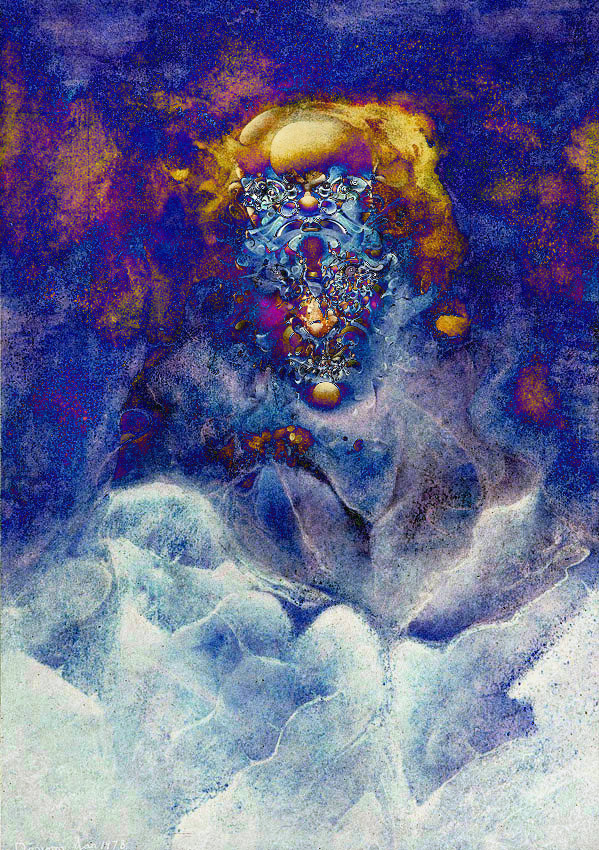

The

books lay piled upon the table, one lay on the matting next

his chair; that whIch he had latest read rested upon Hans

Castorp's stomach and oppressed his breath; yet no order

went from the cortex to the muscles in charge to take it

away. He had read down the page, his chin had sunk upon his

chest, over his innocent blue eyes the lids had fallen. He

beheld the image of life in flower, its structure, its

flesh-borne loveliness. She had lifted her hands from behind

her head, she opened her arms. On their inner side, par-

ticularly beneath the tender skin of the elbow-points, he

saw die blue branchings of the larger veins. These arms were

of unspeak- able sweetness. She leaned above him, she

inclined unto him and bent down over him, he was conscious

of her organic fragrance and the mild pulsation of her

heart. Something warm and tender clasped him round the neck;

melted with desire and awe, he laid his hands upon the flesh

of her upper arms, where the fine-grained skin over the

triceps came to his sense so heavenly cool; and upon his

lips he felt the moist clinging of her kiss.

|